At TUM, researchers designed and built 30 state-of-the-art calibration devices known as POCAMs (Precision Optical Calibration Modules). These instruments will substantially enhance IceCube’s ability to reconstruct neutrino events and to better characterize the optical properties of the Antarctic ice. Partner institutions contributed complementary technologies, including novel detection units such as the mDOM (multi-PMT Digital Optical Module), the D-Egg (Dual optical sensors in an Ellipsoid Glass for Gen2), and several additional calibration and detection modules.

2,600-metre-deep boreholes in Antarctic ice

The devices are encapsulated in glass spheres slightly larger than a basketball and are mounted along a cable to form a “string” of more than 100 spheres. These strings are deployed into individual boreholes drilled approximately 2,600 meters deep into the Antarctic ice. Embedded deep within the glacier, the sensors monitor a permanently dark, transparent environment for faint flashes of light produced by neutrino interactions.

Neutrinos are generated in a wide range of nuclear processes, from reactions in stars to violent astrophysical events. They are nearly massless, electrically neutral, and interact only rarely with matter, making them extraordinarily difficult to detect. IceCube overcomes this challenge by instrumenting a cubic kilometer of Antarctic ice. When a neutrino interacts with an ice molecule, it produces secondary charged particles that emit brief pulses of Cherenkov radiation. Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) capture and amplify this faint light, allowing scientists to infer the energy and direction of the incoming neutrino. Through this technique, neutrinos have become powerful cosmic messengers, offering unique insights into processes across the universe. IceCube, in particular, has established itself as a uniquely powerful observatory, enabling discoveries that cannot be made elsewhere.

“Knowing that our POCAM modules are now frozen into the Antarctic ice and operating inside the world’s largest neutrino telescope gives me chills. Their realization is the result of a long journey, with many brilliant young researchers contributing along the way. With the POCAMs, we will characterize the Antarctic ice with unprecedented precision,” says ORIGINS scientist Elisa Resconi, Professor of Experimental Physics with Cosmic Particles at TUM. “This improved calibration is essential for reconstructing neutrino events with greater accuracy and for unlocking new insights into the high-energy universe.”

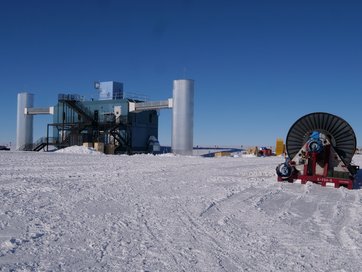

Working at minus 30 °C during the Antarctic summer

“Working at the South Pole is a unique and challenging experience – with temperatures around or below –30 °C, high elevation, and round-the-clock daylight,” says Andrii Terliuk, TUM physicist on the deployment team. “The polar season is short, which makes every day intense as we prepare and deploy the modules into precisely drilled 2.6-kilometer-deep boreholes. But seeing the modules in place and functioning makes it incredibly rewarding.”

The detector modules must withstand extreme temperature and pressure variations during installation and refreezing. Each sensitive instrument is enclosed within a pressure-resistant glass vessel engineered to survive the gradual freezing of the boreholes. To ensure reliable installation, teams conducted full installation rehearsals at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“Deploying each string of sensors into the ice requires focus and teamwork,” adds physicist Colton Hill, the second TUM team member. “It’s physically demanding and technically complex but knowing that these instruments will let us explore the universe in a completely new way makes it all worthwhile.”

The six newly installed Upgrade strings now form the most densely instrumented region of the IceCube detector. The enhanced calibration and detection capabilities will allow researchers to detect more neutrinos and to characterize both the detector and the surrounding ice with unprecedented precision, leading to major improvements in event reconstruction and data analysis.

“It will enable the most precise measurement of atmospheric neutrino oscillations to date,” says Dr. Philipp Eller, senior scientist at TUM, who is also a principal investigator of the ORIGINS Cluster. “Neutrino oscillations are a quantum phenomenon in which neutrinos change from one type to another. By studying them with greater accuracy, we can probe fundamental questions about particle physics and the structure of the universe.”

The IceCube Upgrade is also a crucial step toward IceCube-Gen2, the next-generation neutrino observatory planned for the South Pole. IceCube-Gen2 — designated a national priority research initiative by the German federal government — will expand the detector into a substantially larger facility with world-leading sensitivity across more than ten orders of magnitude in energy.

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Elisa Resconi

Professor of Experimental Physics with Cosmic Particles

TUM School of Natural Sciences / Excellence Cluster ORIGINS

Email: elisa.resconi(at)tum.de

Acknowledgement

The National Science Foundation (NSF) provided primary funding for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, with additional support from partner funding agencies worldwide. The University of Wisconsin–Madison serves as the lead institution and is responsible for the detector’s maintenance and operations. Funding agencies in each collaborating country support their respective scientific research activities.

The IceCube Collaboration comprises approximately 450 physicists from 58 institutions across 14 countries. In Germany, participating institutions include: DESY Zeuthen, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen–Nürnberg, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Ruhr University Bochum, RWTH Aachen University, TU Dortmund University, Technical University of Munich (TUM), University of Münster, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, and University of Wuppertal.

The IceCube Collaboration is currently led by its spokesperson, Erin O’Sullivan, Professor of Physics at Uppsala University, Sweden.